Introduction

To understand economics one must understand consumption theory. Why? We will see that it involves extensive areas in economics and politics. Historically, some of the most widely cited works in consumption theory are:

- Adam Smith (1789) on the causes of the wealth of nations and its effect on wage income;

- Keynes (1936) on disequilibrium and “forced” saving;

- Clower (1965) on notional vs realized income;

- Modigliani (1954) and Friedman (1957) on life-cycle and permanent income hypotheses;

- Lucas (1973) on unpredictable policy changes affecting consumption forecasting;

- Hall (1978) on randomness of consumption;

The objective here is to improve the understanding of:

- The short and long run relationship between consumption and income and/or saving;

- The predictability of saving;

- What factors affect this predictability;

- Practical applications.

Consumption theory deals with three variables: income, consumption and savings.

By definition, savings = income - consumption

Since consumption is by far the largest component of GDP, it is often mentioned as the primary reason for studying consumption theory. However, there is a multitude of variables that affect income and how it affects consumption and saving. That is the Keynes’ General Theory line of thought. In the late 1970s, Hall’s Random-Walk Hypothesis proposed an opposite hypothesis, where consumption is in effect independent of income and dependent only on its prior consumption.

Micro-foundation economics applies an optimization technique called Euler equation on a utility function and subject to a budget constraint, reaching the conclusion that consumption is a function of the summation of present and infinite number of future incomes. At first, this result appears to support the Modigliani’s Life-Cycle Hypothesis and Friedman’s Permanent Income Hypothesis. Further, by assuming that the budget constraint is always satisfied in the consumption model, i.e., consumers don’t spend more than their actual income and assets, Hall reached the conclusion that consumption at time t +1 is only dependent on consumption at time t plus a random variable.

Let’s do a simple calculation where each income, by simplicity, is assumed to be exactly Y and that the summation of all income converges. As such, consumption is a function of nY, where n tends to infinite. To reach Hall’s conclusion, Flavin (1981) also assumed budget constraint is satisfied at time t+1 so consumption at t+1 is a function of the exactly the same nY. The difference between consumption at t +1 and t is nY – nY, which is zero. Thus consumption at t +1 is dependent only on consumption at t.

In contrast, Wu (1994, 2016) showed that, as the consumer ages, the summation of income at t+1 after the loss of one period of consumer’s income should be (n-1)Y, where n tends to infinite. Thus, the difference in consumption between t+1 and t is Y and change in saving is a function of income growth. This is a direct application of Clower’s Dual-Decision Hypothesis and a challenge to Hall’s lifetime budget constraint assumption. Wu (2016) has shown that the same summation equation in the long form for consumption at t+1 can be written in Σ notation for both Hall (n → ∞) and Wu ((n-1) → ∞) approaches by varying the lower limit of the summation index from 0 to 1.

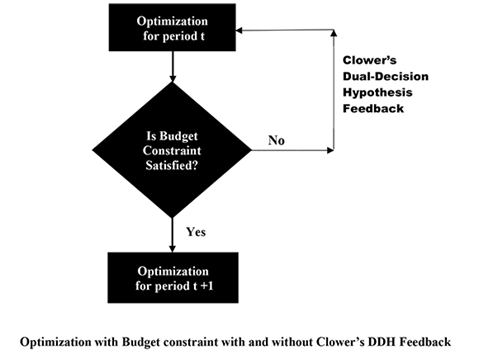

Fundamentally, it all comes down to the budget constraint assumption: Hall assumes it to be always satisfied while Clower argues that it does not always do. In other words, how does different budget constraint assumptions affect the outcome of consumption theory and how does it work in practice? Wu (2017) has illustrated the Hall and Keynes-Clower-Wu approaches as,

In spite of using the wrong optimization technique, we will see that Keynes assumed a "simple principle" leads to the mathematical conclusion on change in savings. To prove Keynes' insight, we must apply Clower's Dual-Decision Hypothesis. Wu's proof is that change in saving is a function of change of income or income growth. This result also questions Modigliani's Life-Cycle Hypothesis and Friedman's Permanent Income Hypothesis. It shows that Keynes' principle and Lucas' Critique on consumption reached the same conclusion, 40 years apart. Because of an implausible assumption that budget constraint is always satisfied, this helps explain why Hall's consumption result couldn't hold in data.

We will see that consumption theory has at least two important applications: 1. While the Trump administration I and II trade policy emphasizes the effect of trade deficit on manufacturing, the consequence of a more balanced trade should result in an increase in income and saving, which is predicted by Keynes-Clower-Wu consumption theory. 2. Due to a skewed electoral college system in the U.S. favoring farm states, farmers optimize their choice of president by selecting whoever is more likely to increase their future income, i.e., making the selection a president no more different than the "consumption" of any other service.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Here is the summary provided by Google Gemini on the difference between Hall and Cheng K Wu consumption theory:

conceptual difference table between Hall and cheng k wu consumption theory

This table details the specific theoretical divergence between Robert Hall’s Random Walk Hypothesis (based on the Permanent Income Hypothesis) and Cheng K. Wu’s Theory of Consumption (based on Clower’s Dual-Decision Hypothesis).

Conceptual Difference Table: Hall vs. Wu

| Feature | Robert Hall (Random Walk / PIH) | Cheng K. Wu (Feedback / DDH) |

| Core Principle | Consumption Smoothing: Agents maintain a stable consumption path over their lifetime. | Feedback Optimization: Agents constantly re-optimize based on realized income growth constraints. |

| Primary Driver | Unexpected Shocks: Consumption only changes in response to unpredictable news about future wealth. | Income Growth Rate: Changes in savings are functionally driven by the rate of change in realized income. |

| View of Savings | Passive Buffer: Savings rise/fall only to absorb temporary income fluctuations to keep consumption smooth. | Active Adjuster: Savings are the primary variable that reacts to "growth shocks" to satisfy the budget constraint. |

| Mathematical Conclusion | Random Walk (ΔCt=ϵt): The change in consumption is unpredictable (stochastic). | Deterministic Function (ΔSt=f(gY)): The change in savings is a predictable function of income growth. |

| Budget Constraint | Always Satisfied: Assumes the agent always stays within their lifetime budget constraint (Market Equilibrium). | Frequently Violated: Realized income often fails to meet the plan, forcing a "Dual Decision" (Disequilibrium). |

| Role of Information | Rational Expectations: Agents perfectly process all available information; only "surprises" matter. | Realized Constraints: Agents may have expectations, but actual cash flow (realized income) dictates the immediate reaction. |

| Forecasting | Impossible: You cannot predict future consumption changes because you cannot predict future news. | Possible: You can predict savings behavior if you observe the trend/volatility of income growth. |

Deep Dive: The "Mathematical Error" Critique

The central conflict between these two theories lies in how they handle the Summation of Future Incomes.

1. Hall's View (The Euler Equation)

Hall argued that a rational consumer estimates their total lifetime wealth (sum of all future incomes) and consumes a fraction of it today.

- The Logic: If I expect my income to grow by 5% next year, I have already factored that into my spending today. Therefore, when that 5% growth actually happens, my spending won't change. My spending only changes if the growth is 0% (shock) or 10% (shock).

- Result: ΔC is random.

2. Wu's Critique (The "New Result")

Wu re-derived the mathematical summation used by Hall (and later Marjorie Flavin) and argued there was an oversight in the algebra regarding the "index of summation."

- The Logic: Wu argues that you cannot mathematically separate the change in savings from the growth of income. When realized income growth slows down, the mathematical condition for the budget constraint is violated.

- The Mechanism (DDH): Because the constraint is violated, the consumer effectively "cancels" their previous life plan and makes a new one (Dual-Decision).

- Result: The "change in savings" is not random; it is mathematically forced to track the deceleration or acceleration of income.

Visual Analogy

- Hall’s Consumer is like a ship on Autopilot. It has a set course (lifetime plan). It only moves the rudder (changes consumption) if a rogue wave (unexpected shock) hits it. If the sea is calm, the rudder stays still.

- Wu’s Consumer is like a driver in Heavy Traffic. They have a destination (plan), but they are constantly hitting the brakes or gas (changing savings) based on the speed of the car in front of them (income growth). Their behavior is a direct, predictable function of the traffic speed, not just "random" shocks.